Music Theory - Grade 1

by JazzMaverick (Jun 18, 2009)

This is for those who want to be graded, or for those who are just generally keen on learning.

This lesson took FOREVER to write because I needed to write out each example over and over again, apologies for the long wait!

---------------------------------------------------------------

To start things off before we get into the grading; in order to fully understand these basics, it's important you already know the following:

- Major scale

- Minor scale

- Major Keys (sharps and flats)

- Able to read the notes on notation. (even though I cover them)

If you do not already know this... please look back at my lessons:

Major Scale & Modes

And look at the first position - The Ionian (Major) Scale.

Also:

Keys

And look at the first one again.

If you don't know how to read notation, I recommend you visit: Music Theory

---------------------------------------------------------------

So, let's start!

This should cover close to all of the requirements for the official grading from companies, but each year supplies new targets and expectations, so keep that in mind.

We're all familiar with the notes A - G, but just incase, in Music we refer to our musical notes from seven letters in the alphabet, these are repeated and they represent the same notes at a higher/lower level.

The Octave (eight) is the term for the same note, higher or lower containing the same letter name. E.G. A-A, D#-D#, etc.

The word "Pitch" is used to describe how high or how low a sound is, and in music this is shown with Notes:

etc.

These notes are placed on the Stave.

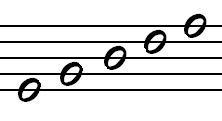

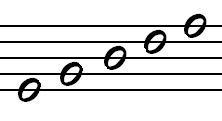

The Stave consists of a series of five parallel lines. Notes can be placed on the lines or in the spaces between them. The lines and spaces are always reckoned from the lowest upwards.

Lines:

Spaces:

All of these notes can have no certain pitch or name until some distinguishing mark is placed at the beginning of the stave. The mark is called a Clef (which translated means "Key") and the clef then lets you know what notes are what on the Stave.

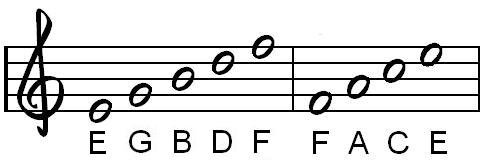

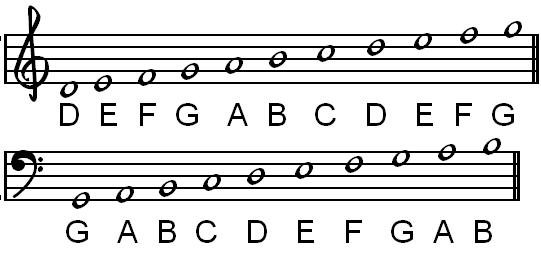

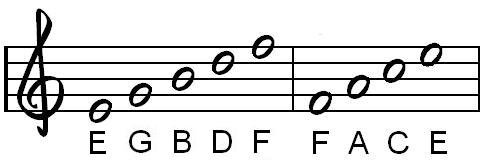

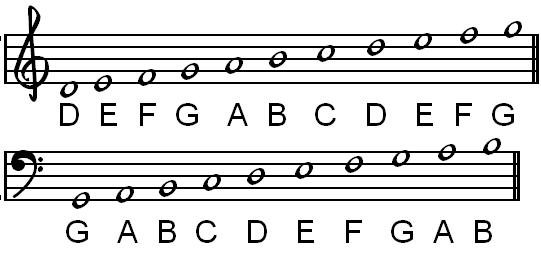

Treble Clef

The Treble Clef, which was originally a capital G, circles round the second line and fixes that line as G, so any note on that line represents the note G. Originally the Treble clef was known as G clef. Now because this clef is placed here, we are now able to define what the pitch is.

Treble Clef:

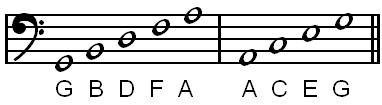

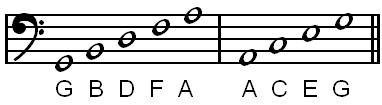

Bass Clef

The Bass Clef contains two dots, these dots are always either side of the fourth line, which defines F. Originally the bass clef used to be a big F. But now the bass clef is written like this:

The notes which are on the bass clef are:

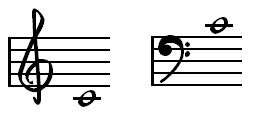

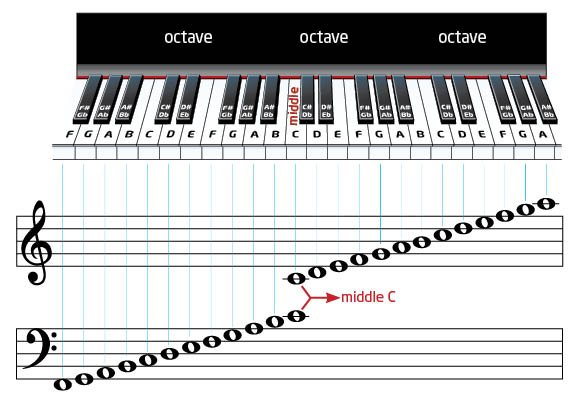

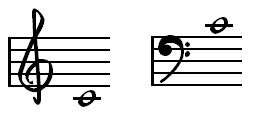

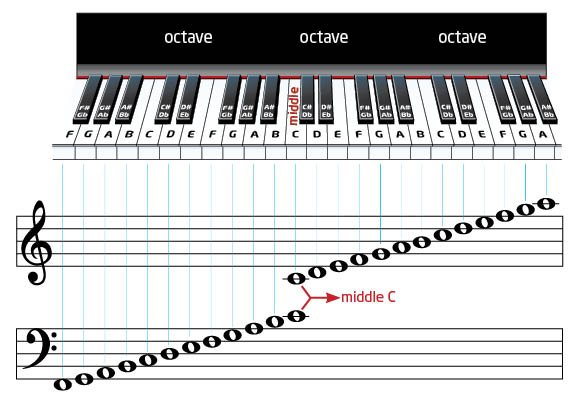

So now that we've seen these notes, there's one note that's missing from both of these clefs, that's "Middle C". It's called middle C because it's the note which is nearest to the middle of the piano. It's written on a line bolow the Treble and a line above the Bass.

So both of these clefs (with the exception of middle C, because it's outside of the Stave) will be:

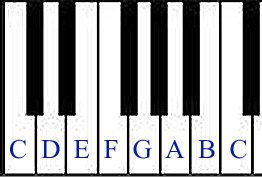

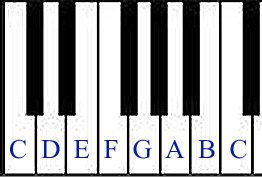

All of these notes I've just shown you can be shown on all of the white keys on a piano.

The smallest distance between two notes on the keyboard is called a semitone. There are semitones in the picture above; C-C#, C#-D, E-F, etc.

A Tone consists of two semitones; C-D, E-F#, G#-A#, etc.

Sharps, Flats and Naturals

The Sharp (#) raises a note one semitone in pitch:

The Flat (♭) lowers a note one semitone:

And The Natural (♮) returns the note to it's original note:

I'm sure most of us know what a scale is, but for those who don't: A scale is a group of notes which can be ascending or descending from the starting note. It depends on the key to determine what scale is going to be used.

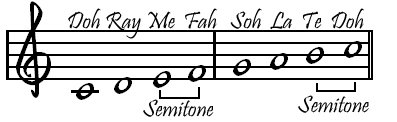

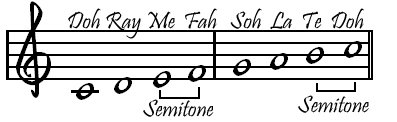

So let's start with C, the white notes on a piano all form a scale known as the Major Scale (this is the only scale I'll be talking about for this lesson by the way)

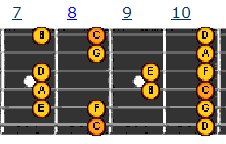

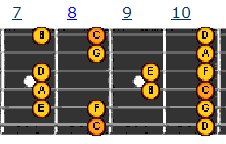

How to play this on guitar:

Think of it like a position where you keep your hand still and each finger is tied to that individual fret. So the 7th fret's notes will always be played with the first finger, the 8th fret's notes will always be played with the middle finger, 9th the ring finger, and 10th with the little finger. On this site, as I hope you already know, the low E is always the bottom string and the high E is always the top string.

Now on notation, these eight notes can be divided into two groups, each have four notes. This is known as a Tetrachord. Which is the Greek term; tetra meaning four, chorde meaning string or note.

So as you can see, the two semitones are in the same place, and between all other notes the interval is a tone.

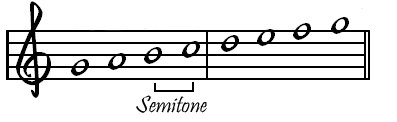

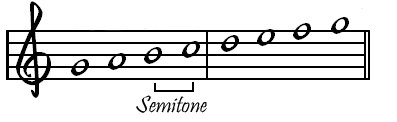

Now we can move onto the second of the two tetrachords, which may now be taken to form the first or lower tetrachord of a new major scale. All you need to do (in notation) is to add four notes above it. Like so:

But in order to preserve the correct order of tones and semitones, the distance between the third and fourth notes of the second tetrachord should be a semitone, not a tone. So for us to correct this notated piece, we need to put a sharp (#) before the F to raise it a semitone.

Therefore, in every major scale, except C Major, there's at least one note which will need to be sharpened or flattened whenever it occurs, this is necessary for us to preserve the correct order of tones and semitones.

But then, if we were to sharpen or flatten notes each time they occur, it would just get complicated and very confusing, so the sharps or flats are grouped together and written immediately after the clef at the beginning of each line. This is what indicated the key; which is the set notes of which the piece is built, with each note having a definite relation to a note known as the key-note. The group of sharps or flats is called the Key-signature

So any sharps or flats occurring in the course of a piece other than in the key-signature are called accidentals.

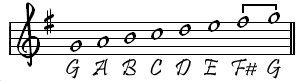

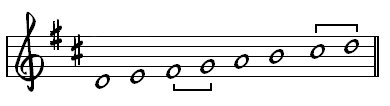

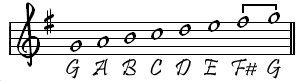

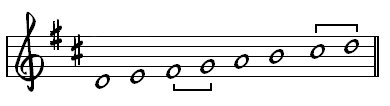

So when it comes to the G Major scale, it can then be written like this:

!!!NOTE!!!

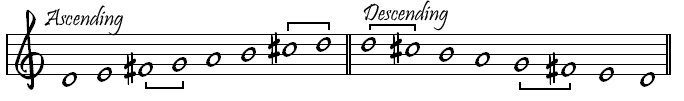

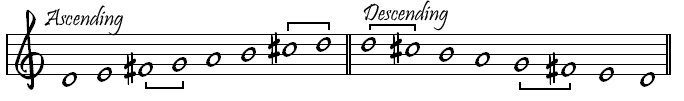

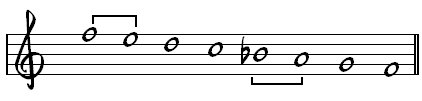

If you're thinking about taking an exam in music theory you should know that you're sometimes asked to write a scale without key-signatures. So if that happens, write out the notes of the scale needed (e.g. D Major) and place the accidentals before those notes which need them. Like so:

If you were to write D Major with a key-signature, you would then write it like this:

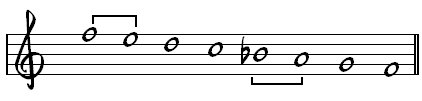

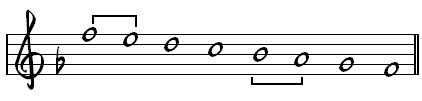

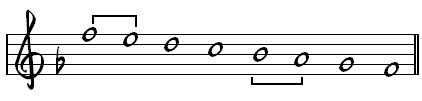

F Major without key-signature:

F Major with key-signature:

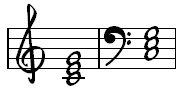

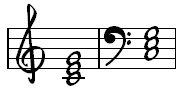

The Tonic is the key note, the root note. The tonic triad in a major key is a chord of three notes, consisting of the tonic, third and fifth of the scale (doh-me-soh).

Tonic Triad of C Major:

As you can see from this image, if the tonic is on a line, then the other two notes will be on the next two notes above; similarly, if the tonic is on a space, then the two remaining notes will be on the two spaces directly above the key-note. Like so:

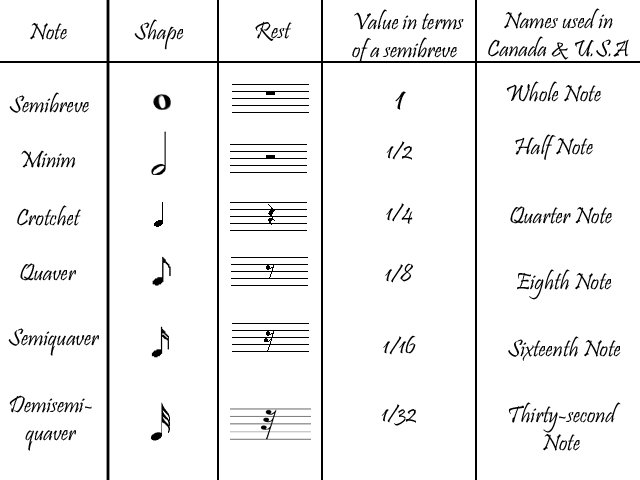

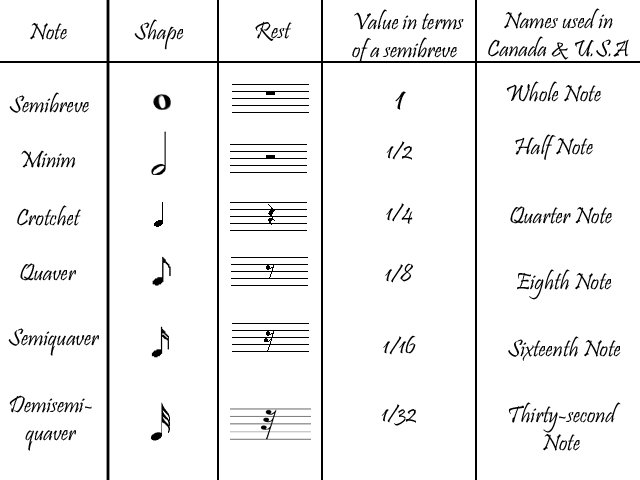

Time Values of Notes

The length of sounds is shown by notes of different shapes, which I mentioned near the beginning of the lesson. Periods of silence are shown by signs called Rests.

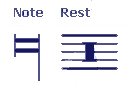

There are four other notes which I haven't put on here because they aren't used in modern time, but just so you know what they are:

Longa (AKA Quadruple Whole Note):

This is 4 times as long as a Semibreve.

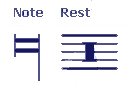

A Breve (AKA Double Whole Note):

This is twice as long as a Semibreve. It's Rest note is:

A Hemidemisemiquaver (AKA sixty-fourth note):

This is the second fastest note in notation. It's Rest is:

A Quasihemidemisemiquaver (AKA one hundred and twenty eighth note):

The reason why the four of these are no longer used in modern times is because they're too slow and fast for modern music, which is why it died out around the romantic era.

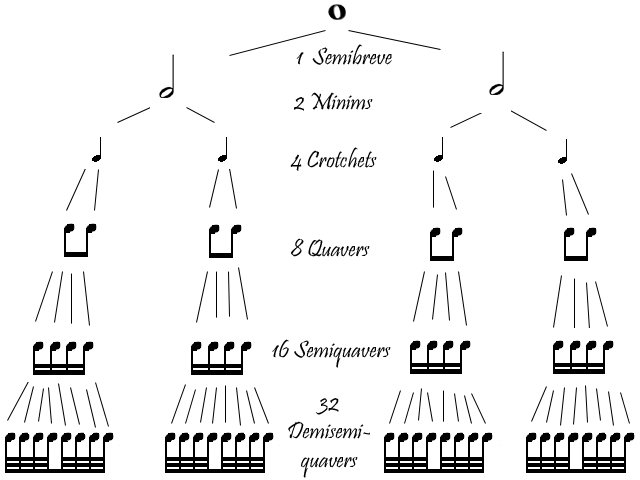

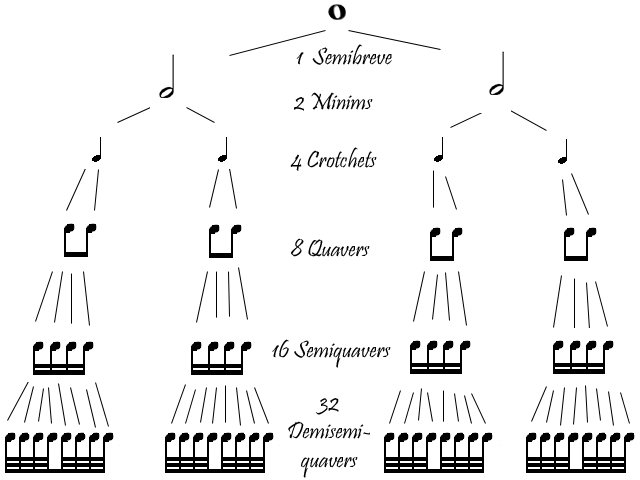

A now here's a table showing the number of notes which are broken down from one semibreve:

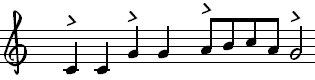

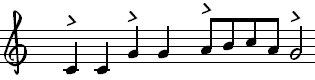

When we listen to music, usually we can feel a place where we can usually clap. This is called the Pulse or Beat of the music.

If you listen closely to some songs in music, some beats can be stronger than others, and those are called Accents.

The beats almost always fall into a regular group of two or three, the first of each group being an accent.

The number of beats from one accent to the other splits the music into equal measures, each of which is called a Bar. In order for us to know where these splits are, a line is placed across the stave, which is called a Bar-line.

This tune will therefore be in two time.

This will be in three time.

At the end of a piece of music, or a section of a piece, two bar-lines are placed across the stave. It's called a Double Bar. The time of a piece of music is shown by the Time-Signature, and this is ALWAYS placed immediately after the key-signature at the beginning of the piece.

So by looking at these time-signatures, you can see that the numbers are placed one above the other. For now, it's best to think of the top number as showing how many beats there are in a bar, and the bottom number as the value of each beat.

So, 2/4 indicates that there are two crotchet beats in each bar. Similarly 3/2 means that there will be three minim beats in each bar.

So, in the two examples I mentioned a little bit before, 2/4 indicates that there will be two crotchet beats in each bar, and 3/2 indicates that there will be three minim beats in each bar.

Similarly,

3/8 means three quaver beats in a bar.

3/4 means three crotchet beats in a bar.

4/4 means four crotchet beats in a bar.

2/2 means two minim beats in a bar.

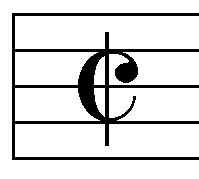

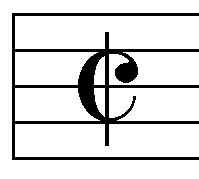

4/4 time is also known as Common Time especially in old music, and instead of figures (4/4) it's shown by the sign "C". Here's where I should point out that C is not a capital letter for Common Time. In early days music in three time was represented by O, the circle or symbol of perfection; music in two or four time by C, the imperfect or incomplete circle.

2/2 time is often called Alla Breve, and is shown by the sign:

I advise you not to use these old signs, even though their meaning should be known, but they often lead to confusion. There can, however, be no doubt about:

4/4 (four crotchet beats in a bar)

2/2 (two minim beats in a bar)

4/2 (four minim beats in a bar)

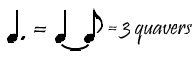

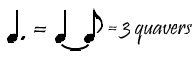

The value of a note or rest can be increased by placing a dot after it. The effect of the dot is to increase the length of the note or rest by half its original value.

Therefore, is equal to the value of 3 quavers.

is equal to the value of 3 quavers.

is equal to the value of 3 semiquavers.

is equal to the value of 3 semiquavers.

The value of a note may also be increased:

1) By a Tie or Bind.

= a crotchet plus a quaver. The first note only is sounded, but it's held on for its own length plus that of the following tied note.

= a crotchet plus a quaver. The first note only is sounded, but it's held on for its own length plus that of the following tied note.

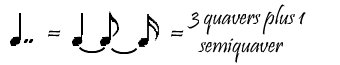

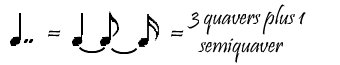

2) By placing two dots after the original note:

The effect of the first dot is to increase the value of the note by half, and the second dot adds again half the value of the first dot.

The effect of the first dot is to increase the value of the note by half, and the second dot adds again half the value of the first dot.

Like so:

Here's a table showing simple time signatures, which are ordinary notes like minim, crotchet, etc. The rest will be explained later on.

Since pictures can only do so much, I'll record a few examples so you can definitely understand the Time Signatures...

Note, these are all the same tempo; 120 BPM (beats per minute).

2 2 Minim Example Even though I've put four notes in here, you only need to count 2 beats, so it's: 1, 2, 1, 2 (and so on)

2/4 Crotchet Example

2/8 Quaver Example

3/2 Minim Example

3/4 Crotchet Example

3/8 Quaver Example

4/2 Minim Example

4/4 Crotchet Example

4/8 Quaver Example

Hopefully it'll make more sense now.

If a passage contains sharp accidentals only, you then need to find which sharp is the last in the key-signature order. The order of sharps (only two for this grade) are:

The last sharp is always the seventh degree of the scale, so the key-note will be a semitone above.

The last sharp in order in the above tune is C sharp; therefore the key-note (a semitone above) will be D, and the key D Major, because of the presence of F sharp in the tune.

But, if a passage only has flats (there's only one flat key in this grade) the key-note will be four notes below this flat.

The flat is B flat, therefore the key will be F Major.

WARNING!!!!!

A tune does not necessarily begin or end on the key-note. The second last tune (D Major example) does neither. The last tune ends on the key-note, but doesn't begin on it. Make sure you keep that in mind at all times!

So, this is all I'm going to cover for this grade, to learn the Italian words and abbreviations along with signs which are likely to be found in the music set for Grade 1, please look at my other lesson here: Music Theory - Grade 1 - Terms and Signs

As time goes on, this will be easier to remember, but for now, just keep recapping everything I've covered. Good Luck!

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Also, check out my music listed on Sound Cloud (link below) if you like it follow me on facebook! :)

JazzMaverick on Sound Cloud

JazzMaverick Music

__________________________________________________________________________________________

This lesson took FOREVER to write because I needed to write out each example over and over again, apologies for the long wait!

---------------------------------------------------------------

To start things off before we get into the grading; in order to fully understand these basics, it's important you already know the following:

- Major scale

- Minor scale

- Major Keys (sharps and flats)

- Able to read the notes on notation. (even though I cover them)

If you do not already know this... please look back at my lessons:

Major Scale & Modes

And look at the first position - The Ionian (Major) Scale.

Also:

Keys

And look at the first one again.

If you don't know how to read notation, I recommend you visit: Music Theory

---------------------------------------------------------------

So, let's start!

This should cover close to all of the requirements for the official grading from companies, but each year supplies new targets and expectations, so keep that in mind.

The Stave (or Staff)

We're all familiar with the notes A - G, but just incase, in Music we refer to our musical notes from seven letters in the alphabet, these are repeated and they represent the same notes at a higher/lower level.

The Octave (eight) is the term for the same note, higher or lower containing the same letter name. E.G. A-A, D#-D#, etc.

The word "Pitch" is used to describe how high or how low a sound is, and in music this is shown with Notes:

etc.

These notes are placed on the Stave.

The Stave consists of a series of five parallel lines. Notes can be placed on the lines or in the spaces between them. The lines and spaces are always reckoned from the lowest upwards.

Lines:

Spaces:

G and F Clefs

All of these notes can have no certain pitch or name until some distinguishing mark is placed at the beginning of the stave. The mark is called a Clef (which translated means "Key") and the clef then lets you know what notes are what on the Stave.

Treble Clef

The Treble Clef, which was originally a capital G, circles round the second line and fixes that line as G, so any note on that line represents the note G. Originally the Treble clef was known as G clef. Now because this clef is placed here, we are now able to define what the pitch is.

Treble Clef:

Bass Clef

The Bass Clef contains two dots, these dots are always either side of the fourth line, which defines F. Originally the bass clef used to be a big F. But now the bass clef is written like this:

The notes which are on the bass clef are:

So now that we've seen these notes, there's one note that's missing from both of these clefs, that's "Middle C". It's called middle C because it's the note which is nearest to the middle of the piano. It's written on a line bolow the Treble and a line above the Bass.

So both of these clefs (with the exception of middle C, because it's outside of the Stave) will be:

All of these notes I've just shown you can be shown on all of the white keys on a piano.

The smallest distance between two notes on the keyboard is called a semitone. There are semitones in the picture above; C-C#, C#-D, E-F, etc.

A Tone consists of two semitones; C-D, E-F#, G#-A#, etc.

Sharps, Flats and Naturals

The Sharp (#) raises a note one semitone in pitch:

The Flat (♭) lowers a note one semitone:

And The Natural (♮) returns the note to it's original note:

Construction of the Major Scale

I'm sure most of us know what a scale is, but for those who don't: A scale is a group of notes which can be ascending or descending from the starting note. It depends on the key to determine what scale is going to be used.

So let's start with C, the white notes on a piano all form a scale known as the Major Scale (this is the only scale I'll be talking about for this lesson by the way)

How to play this on guitar:

Think of it like a position where you keep your hand still and each finger is tied to that individual fret. So the 7th fret's notes will always be played with the first finger, the 8th fret's notes will always be played with the middle finger, 9th the ring finger, and 10th with the little finger. On this site, as I hope you already know, the low E is always the bottom string and the high E is always the top string.

Now on notation, these eight notes can be divided into two groups, each have four notes. This is known as a Tetrachord. Which is the Greek term; tetra meaning four, chorde meaning string or note.

So as you can see, the two semitones are in the same place, and between all other notes the interval is a tone.

Now we can move onto the second of the two tetrachords, which may now be taken to form the first or lower tetrachord of a new major scale. All you need to do (in notation) is to add four notes above it. Like so:

But in order to preserve the correct order of tones and semitones, the distance between the third and fourth notes of the second tetrachord should be a semitone, not a tone. So for us to correct this notated piece, we need to put a sharp (#) before the F to raise it a semitone.

Therefore, in every major scale, except C Major, there's at least one note which will need to be sharpened or flattened whenever it occurs, this is necessary for us to preserve the correct order of tones and semitones.

But then, if we were to sharpen or flatten notes each time they occur, it would just get complicated and very confusing, so the sharps or flats are grouped together and written immediately after the clef at the beginning of each line. This is what indicated the key; which is the set notes of which the piece is built, with each note having a definite relation to a note known as the key-note. The group of sharps or flats is called the Key-signature

So any sharps or flats occurring in the course of a piece other than in the key-signature are called accidentals.

So when it comes to the G Major scale, it can then be written like this:

!!!NOTE!!!

If you're thinking about taking an exam in music theory you should know that you're sometimes asked to write a scale without key-signatures. So if that happens, write out the notes of the scale needed (e.g. D Major) and place the accidentals before those notes which need them. Like so:

If you were to write D Major with a key-signature, you would then write it like this:

F Major without key-signature:

F Major with key-signature:

Tonic Triads (In C G D F)

The Tonic is the key note, the root note. The tonic triad in a major key is a chord of three notes, consisting of the tonic, third and fifth of the scale (doh-me-soh).

Tonic Triad of C Major:

As you can see from this image, if the tonic is on a line, then the other two notes will be on the next two notes above; similarly, if the tonic is on a space, then the two remaining notes will be on the two spaces directly above the key-note. Like so:

Time Values of Notes

Dotted Notes and Rests

The length of sounds is shown by notes of different shapes, which I mentioned near the beginning of the lesson. Periods of silence are shown by signs called Rests.

There are four other notes which I haven't put on here because they aren't used in modern time, but just so you know what they are:

Longa (AKA Quadruple Whole Note):

This is 4 times as long as a Semibreve.

A Breve (AKA Double Whole Note):

This is twice as long as a Semibreve. It's Rest note is:

A Hemidemisemiquaver (AKA sixty-fourth note):

This is the second fastest note in notation. It's Rest is:

A Quasihemidemisemiquaver (AKA one hundred and twenty eighth note):

The reason why the four of these are no longer used in modern times is because they're too slow and fast for modern music, which is why it died out around the romantic era.

A now here's a table showing the number of notes which are broken down from one semibreve:

When we listen to music, usually we can feel a place where we can usually clap. This is called the Pulse or Beat of the music.

If you listen closely to some songs in music, some beats can be stronger than others, and those are called Accents.

The beats almost always fall into a regular group of two or three, the first of each group being an accent.

The number of beats from one accent to the other splits the music into equal measures, each of which is called a Bar. In order for us to know where these splits are, a line is placed across the stave, which is called a Bar-line.

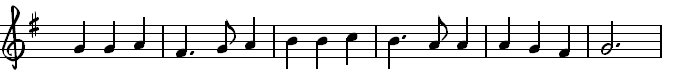

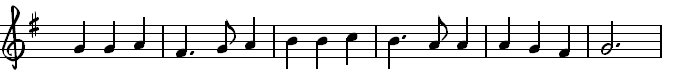

This tune will therefore be in two time.

This will be in three time.

At the end of a piece of music, or a section of a piece, two bar-lines are placed across the stave. It's called a Double Bar. The time of a piece of music is shown by the Time-Signature, and this is ALWAYS placed immediately after the key-signature at the beginning of the piece.

So by looking at these time-signatures, you can see that the numbers are placed one above the other. For now, it's best to think of the top number as showing how many beats there are in a bar, and the bottom number as the value of each beat.

So, 2/4 indicates that there are two crotchet beats in each bar. Similarly 3/2 means that there will be three minim beats in each bar.

So, in the two examples I mentioned a little bit before, 2/4 indicates that there will be two crotchet beats in each bar, and 3/2 indicates that there will be three minim beats in each bar.

Similarly,

3/8 means three quaver beats in a bar.

3/4 means three crotchet beats in a bar.

4/4 means four crotchet beats in a bar.

2/2 means two minim beats in a bar.

4/4 time is also known as Common Time especially in old music, and instead of figures (4/4) it's shown by the sign "C". Here's where I should point out that C is not a capital letter for Common Time. In early days music in three time was represented by O, the circle or symbol of perfection; music in two or four time by C, the imperfect or incomplete circle.

2/2 time is often called Alla Breve, and is shown by the sign:

I advise you not to use these old signs, even though their meaning should be known, but they often lead to confusion. There can, however, be no doubt about:

4/4 (four crotchet beats in a bar)

2/2 (two minim beats in a bar)

4/2 (four minim beats in a bar)

Dotted Notes and Rests

The value of a note or rest can be increased by placing a dot after it. The effect of the dot is to increase the length of the note or rest by half its original value.

Therefore,

is equal to the value of 3 quavers.

is equal to the value of 3 quavers. is equal to the value of 3 semiquavers.

is equal to the value of 3 semiquavers.The value of a note may also be increased:

1) By a Tie or Bind.

= a crotchet plus a quaver. The first note only is sounded, but it's held on for its own length plus that of the following tied note.

= a crotchet plus a quaver. The first note only is sounded, but it's held on for its own length plus that of the following tied note.2) By placing two dots after the original note:

The effect of the first dot is to increase the value of the note by half, and the second dot adds again half the value of the first dot.

The effect of the first dot is to increase the value of the note by half, and the second dot adds again half the value of the first dot. Like so:

Here's a table showing simple time signatures, which are ordinary notes like minim, crotchet, etc. The rest will be explained later on.

Since pictures can only do so much, I'll record a few examples so you can definitely understand the Time Signatures...

Note, these are all the same tempo; 120 BPM (beats per minute).

2 2 Minim Example Even though I've put four notes in here, you only need to count 2 beats, so it's: 1, 2, 1, 2 (and so on)

2/4 Crotchet Example

2/8 Quaver Example

3/2 Minim Example

3/4 Crotchet Example

3/8 Quaver Example

4/2 Minim Example

4/4 Crotchet Example

4/8 Quaver Example

Hopefully it'll make more sense now.

Finding The Key Of A Melody

If a passage contains sharp accidentals only, you then need to find which sharp is the last in the key-signature order. The order of sharps (only two for this grade) are:

The last sharp is always the seventh degree of the scale, so the key-note will be a semitone above.

The last sharp in order in the above tune is C sharp; therefore the key-note (a semitone above) will be D, and the key D Major, because of the presence of F sharp in the tune.

But, if a passage only has flats (there's only one flat key in this grade) the key-note will be four notes below this flat.

The flat is B flat, therefore the key will be F Major.

WARNING!!!!!

A tune does not necessarily begin or end on the key-note. The second last tune (D Major example) does neither. The last tune ends on the key-note, but doesn't begin on it. Make sure you keep that in mind at all times!

So, this is all I'm going to cover for this grade, to learn the Italian words and abbreviations along with signs which are likely to be found in the music set for Grade 1, please look at my other lesson here: Music Theory - Grade 1 - Terms and Signs

As time goes on, this will be easier to remember, but for now, just keep recapping everything I've covered. Good Luck!

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Also, check out my music listed on Sound Cloud (link below) if you like it follow me on facebook! :)

JazzMaverick on Sound Cloud

JazzMaverick Music

__________________________________________________________________________________________